|

This page is designed to support the book, "The Theoretical Minimum" by Leonard Susskind and George Hrabovsky. This book will be released by Basic Books in North America, and Penguin Press in the UK on 29 January 2013.

This site will contain material to support those interested in the book. This will include hints and detailed solutions to the practice problems and additional materials that did not fit, or could not be used in the book.

|

A world-class physicist and a citizen scientist combine forces to teach Physics 101—the DIY way.

The Theoretical Minimum is a book for anyone who has ever regretted not taking physics in college—or who simply wants to know how to think like a physicist. In this unconventional introduction, physicist Leonard Susskind and citizen-scientist George Hrabovsky offer a first course in physics and associated math for the ardent amateur. Unlike most popular physics books—which give readers a taste of what physicists know but shy away from equations or math—Susskind and Hrabovsky actually teach the skills you need to do physics, beginning with classical mechanics, yourself. Based on Susskind’s enormously popular Stanford University-based (and YouTube-featured) continuing-education course, the authors cover the minimum—the theoretical minimum of the title—that readers need to master to study more advanced topics.

Somewhere in Steinbeck country two tired men sit down at the side of the road. Lenny combs his beard with his fingers and says, “Tell me about the laws of physics, George.” George looks down for a moment, then peers at Lenny over the tops of his glasses. “Okay, Lenny, but just the minimum.”

An alternative to the conventional go-to-college method, The Theoretical Minimum provides a tool kit for amateur scientists to learn physics at their own pace.

Note: This book was written and typeset in Mathematica versions 7, 8, and 9.

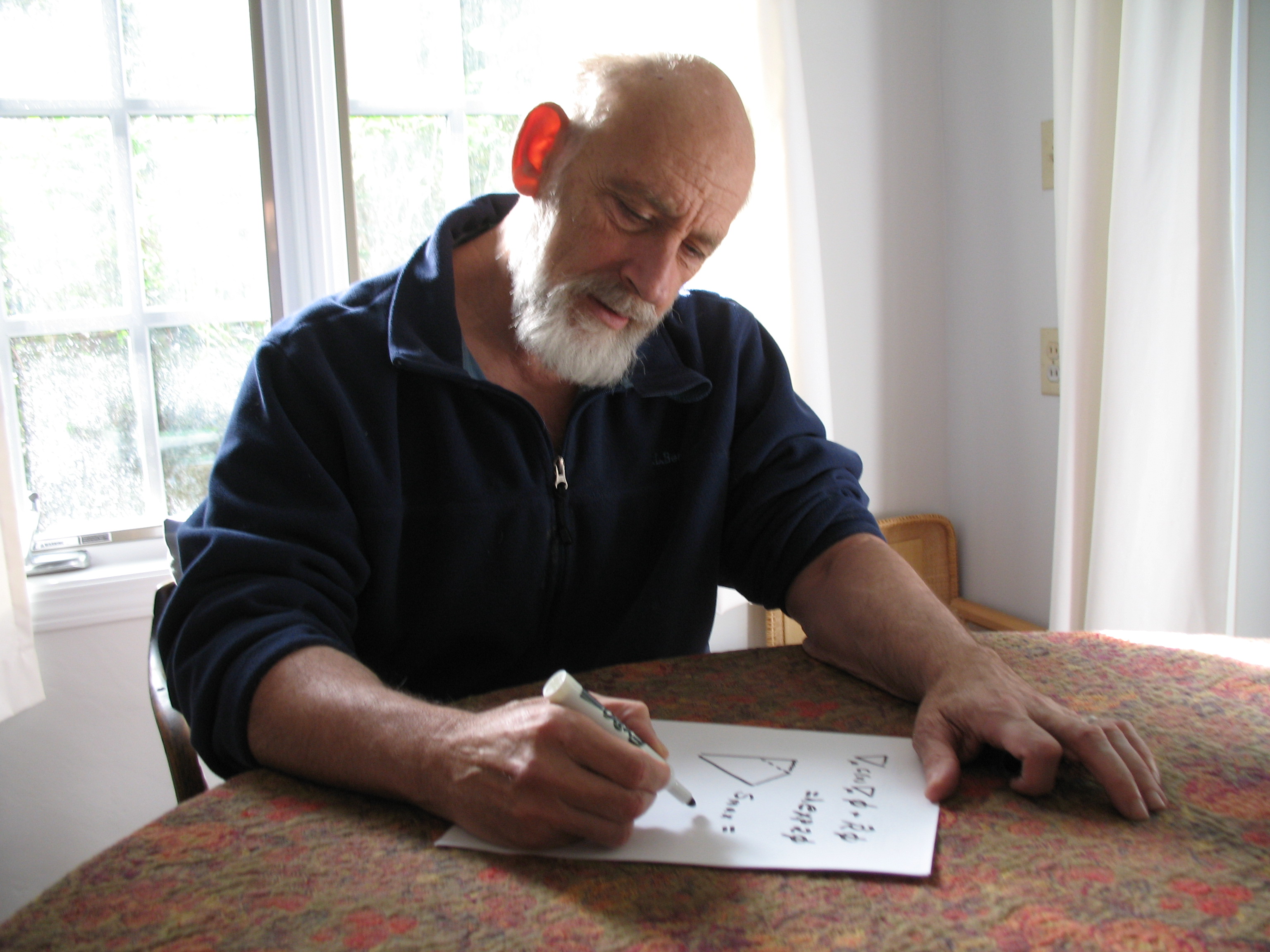

Leonard Susskind has been the Felix Bloch Professor in Theoretical Physics at Stanford University since 1978. The author of The Black Hole War and The Cosmic Landscape, he lives in Palo Alto, California.

George Hrabovsky is the president of Madison Area Science and Technology (MAST), a nonprofit organization dedicated to scientific and technological research and education. He lives in Madison, Wisconsin.

ADVANCE PRAISE FOR The Theoretical Minimum

“What a wonderful and unique resource. For anyone who is determined to learn physics for real, looking beyond conventional popularizations, this is the ideal place to start. It gets directly to the important points, with nuggets of deep insight scattered along the way. I'm going to be recommending this book right and left.”

—Sean Carroll, physicist, California Institute of Technology, and author of The Particle at the End of the Universe

"Readers ready to embrace their inner applied mathematician will enjoy this brisk, bare-bones introduction to classical mechanics drawn from Stanford University’s “Continuing Studies” program. Although physicist Susskind (The Black Hole War) and science advocate Hrabovsky touch briefly on electricity and magnetism, the book is primarily about mechanics and the motion of particles. The authors open with a look at closed and open systems and the reversibility of physical laws, a concept central to the field. Next are rigorous chapters on trigonometry and vectors, and a no-nonsense intro to differential and integral calculus, and how these tools are used to calculate the motion of objects through space. Not for the faint of heart, successive chapters introduce Newton’s law of motion, the complex mathematics of “systems” of particles, phase space, conservation of momentum, and the Principle of Least Action, which allows scientists to “package” a system’s velocity, mass, direction, and forces into a single function. The authors intend this book as a toolkit for determined readers who want to teach themselves basic mechanics. Although their discussions are clear enough, even the hardiest reader will want to bring a basic calculus text along for the journey. 62 line drawings."

—Publishers Weekly

Click here to visit the MAST web site.

I’ve always enjoyed explaining physics. For

me it’s much more than teaching: It’s a way

of thinking. Even when I’m at my desk doing

research, there’s a dialog going on in my

head. Figuring out the best way to explain

something is almost always the best way to

understand it yourself.

About ten years ago someone asked me if I

would teach a course for the public. As it

happens, the Stanford area has a lot of people

who once wanted to study physics, but life

got in the way. They had had all kinds of

careers but never forgot their one-time infatuation

with the laws of the universe. Now, after

a career or two, they wanted to get back

into it, at least at a casual level.

Unfortunately there was not much opportunity

for such folks to take courses. As a rule,

Stanford and other universities don’t allow

outsiders into classes, and, for most of

these grown-ups, going back to school as

a full-time student is not a realistic option.

That bothered me. There ought to be a way

for people to develop their interest by interacting

with active scientists, but there didn’t

seem to be one.

That’s when I first found out about Stanford’s

Continuing Studies program. This program

offers courses for people in the local nonacademic

community. So I thought that it might just

serve my purposes in finding someone to explain

physics to, as well as their purposes, and

it might also be fun to teach a course on

modern physics. For one academic quarter

anyhow.

It was fun. And it was very satisfying in

a way that teaching undergraduate and graduate

students was sometimes not. These students

were there for only one reason: Not to get

credit, not to get a degree, and not to be

tested, but just to learn and indulge their

curiosity. Also, having been “around the

block” a few times, they were not at all

afraid to ask questions, so the class had

a lively vibrancy that academic classes often

lack. I decided to do it again. And again.

What became clear after a couple of quarters

is that the students were not completely

satisfied with the layperson’s courses I

was teaching. They wanted more than the Scientific American experience. A lot of them had a bit of background,

a bit of physics, a rusty but not dead knowledge

of calculus, and some experience at solving

technical problems. They were ready to try

their hand at learning the real thing—with

equations. The result was a sequence of courses

intended to bring these students to the forefront

of modern physics and cosmology.

Fortunately, someone (not I) had the bright

idea to video-record the classes. They are

out on the Internet, and it seems that they

are tremendously popular: Stanford is not

the only place with people hungry to learn

physics. From all over the world I get thousands

of e-mail messages. One of the main inquiries

is whether I will ever convert the lectures

into books? The Theoretical Minimum is the answer.

The term theoretical minimum was not my own

invention. It originated with the great Russian

physicist Lev Landau. The TM in Russia meant

everything a student needed to know to work

under Landau himself. Landau was a very demanding

man: His theoretical minimum meant just about

everything he knew, which of course no one

else could possibly know.

I use the term differently. For me, the theoretical

minimum means just what you need to know

in order to proceed to the next level. It

means not fat encyclopedic textbooks that

explain everything, but thin books that explain

everything important. The books closely follow

the Internet courses that you will find on

the Web.

Welcome, then, to The Theoretical Minimum—Classical Mechanics, and good luck!

Leonard Susskind

Stanford, California, July 2012

I started to teach myself math and physics

when I was eleven. That was forty years ago.

A lot of things have happened since then—I

am one of those individuals who got sidetracked

by life. Still, I have learned a lot of math

and physics. Despite the fact that people

pay me to do research for them, I never pursued

a degree.

For me, this book began with an e-mail. After

watching the lectures that form the basis

for the book, I wrote an e-mail to Leonard

Susskind asking if he wanted to turn the

lectures into a book. One thing led to another,

and here we are.

We could not fit everything we wanted into

this book, or it wouldn’t be The Theoretical Minimum—Classical Mechanics, it would be A-Big-Fat-Mechanics-Book.

That is what the Internet is for: Taking

up large quantities of bandwidth to display

stuff that doesn’t fit elsewhere! You can

find extra material at the website www.madscitech.org/tm. This material will include answers to the

problems, demonstrations, and additional

material that we couldn’t put in the book.

I hope you enjoy reading this book as much

as we enjoyed writing it.

George Hrabovsky

Madison, Wisconsin, July 2012

Sunday, 10 March 2013: George Hrabovsky will discuss The Theoretical Minimum in specific and amateur science in general at the Madison Science Pub, 2pm at Brocach Irish Pub on Main Street off the Capitol Square in Madison, WI.

Thursday, 21 March 2013: George Hrabovsky will discuss The Theoretical Minimum at the Madison Science Cafe, 5 PM at the Steep and Brew on State Street in Madison WI.

Thursday, 18 April 2013: George Hrabovsky will give a workshop based on the The Theoretical Minimum at Barnes and Noble Bookstore at East Towne Mall, in Madison, WI, at 5 PM.

These files require either Mathematica 8 or later, or the free Mathematica CDF Viewer, though the viewer cannot run the programs, (you can find that here). There will be pdf options in most cases.

As of April 2014 there is a new edition containing all of the errata in the previous document. There is a new errata:

Logic and Proof: A short introduction to the principles of logic and how to construct proofs. (pdf)

An Introduction to Black Holes, Information And The String Theory Revolution

Self-Instruction and Teaching: Science Education for the New Millennium, paperback , hardcover.

For those who are experiencing difficulty with the mathematics, please consult the new course being offered through the MAST website on Elementary Mathematical Methods for Science.